The following is an excerpt from an ongoing conversation with Richard Skelton, the current featured artist on Headphone Community. We have recently discussed his background and early formation, and now it’s time to dive into his composition and sound craft. If you choose to join us, you will find some Bandcamp codes for many of Richard’s albums [although it shouldn’t be the main reason for signing up] and many other exclusive surprises and perks. Join us for a deeper exploration of sonic archaeology…

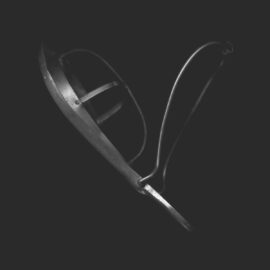

The “broken consort” instruments are modified or handmade. Can you describe specific modifications you’ve made, like string gauge extremes, altered bridges, and deliberately damaged resonance chambers? What does each alteration unlock sonically?

Initially, I’d alter the bridge of a mandola, bouzouki, or banjo from flat to curved so that I could bow individual strings. I’d use a trimmed-down viola bridge, but later I experimented with fashioning them myself. With a guitar, it’s more difficult – rather than replace the saddle, I’d add a “second” bridge – an extremely filed down cello bridge – at the end of the fretboard. Needless to say, this plays havoc with the instrument’s intonation, and raises the profile of the strings so that the fretboard becomes useless, which necessitates learning new playing strategies and techniques.

I’d also experiment with different string types, gauges and tunings, as well as different bowing implements. I might make changes to the instrument itself – adding objects that would either dampen or excite various frequencies: pieces of metal, wood, stone. It’s difficult to go into specifics because it’s a continual process of modification and adjustment, and even the smallest changes can radically alter the sound. More to the point, some of these kinds of modifications can introduce unnatural stresses that can cause permanent damage.

I’ve also experimented with building my own instruments – either from scratch or by repurposing pre-existing objects. Any hollow object has the opportunity to become a resonating chamber. As a consequence, I spend a good amount of time trawling second-hand stores over the years for viable candidates that I can transform into something new.

You use progressively heavier gauge violin strings until you can feel notes reverberating through your body. At what point does physical sensation become more important than what you’re hearing, and does that change what you record?

I think the most primal and affecting form of music is the unaccompanied human voice. When we sing, our body becomes a resonating chamber for our vocal chords. Everything else – the use of instruments – is a proxy. As I’m not a singer, for me at least, instruments are a way of getting as close as I can to that primal experience. In this sense, the pursuit of bodily resonance is both deeply intimate and atavistic. It’s tapping into something ancient.

How does your perspective of music as something physical and alive, rooted in vibration, influence the way you compose or record? Do you try to capture that visceral sense of resonance in your recordings or performance, and if so, how?

As I mentioned previously, I’ve tried to foreground those chance occurrences, those peculiarly human moments that are an index of physical interaction, of felt vibration. From the outset, it was therefore important to me that I played each instrument myself, in whatever way I could, and so my recordings have been defined by my own particular approach to playing. And, as I’ve never owned many instruments, my chief concern has always been to explore their full potential as sound-making devices.

But, in the end, there’s really no way to document or recreate the feeling of playing the instrument itself; not just the sensation of vibration but also the exertion, the pain and discomfort. And, for all that, we musicians (as opposed to singers) are curiously absent from our recordings. In the end, we do not make sound ourselves. It’s the instrument that speaks for us.

You manage to coax unique, resonant textures from string instruments like guitars, violins, and mandolas, layering them into drones and rich harmonies. Do you employ any unusual playing or recording techniques to achieve your signature sound? Were there any specific technical experiments or discoveries that you feel were pivotal in shaping the sonic character of your work?

Yes. I’ve been particularly interested in the principle of sympathetic resonance – the way in which one string will resonate when a particular note on another string is played. A mandola, for example, has eight strings, and so if I used one or two of them as “melody” strings, then the rest can be tuned to resonate when specific notes are sounded. I discovered this effect by simply experimenting with different tunings, but of course, this principle has been built into the design of many folk instruments (which I find very interesting), for example: the Nyckelharpa or Hardanger fiddle.

In general, I think my “signature” sound has evolved from bowing instruments that weren’t intended to be bowed – so in some sense they are all “prepared” through the various modifications that I make. I’ve never been taught to bow conventional instruments, so I don’t know if my techniques are unorthodox, but it must be true that, for example, bowing a bouzouki that is lying flat on a table involves a different technique than bowing a cello upright. I’d say there’s perhaps a more intimate awareness of the effects of gravity upon the bow itself, which I can either resist or exploit to achieve various effects.

Interestingly, it was only years later that I actually acquired a cello, and undoubtedly I’ve brought some of those idiosyncrasies to my playing. I remember working with a string quartet, and, as I don’t write music, I recorded the melodies that each player should perform. The cellist, in particular, had difficulty replicating the textures and tonalities that were an integral part of the composition.

Your degradation techniques involve re-recording through wooden or metal objects, then subjecting those recordings to further distortion. Can you share a bit of the actual signal chain? Are you playing recordings back through contact speakers on specific surfaces, or something else entirely?

Yes, with my work as The Inward Circles I was interested in the processes of physical decay, so it made sense to explore what happens to sound as it decays in real-world contexts. When sound is transmitted through physical objects, it is transformed and deformed in interesting ways. Sometimes it was simply a case of playing the source material loudly through speakers, and using contact microphones to record how various objects resonated in sympathy. I would also attach speaker cones directly to surfaces, so that I was directly recording only the vibrations. I’d then rebroadcast the results through different objects, and so on. Pretty soon, the sounds are transformed beyond recognition.

You’ve also left instruments outside on the moors to weather, and even buried a violin in peat and then exhumed it to record its altered voice. What drives you to “collaborate” with the environment in these ways? What have you learned from allowing natural processes, like time, weather, and decay, to literally shape the sounds you use in your music?

During the early years of Sustain-Release, I began visiting and revisiting places that had undergone some form of transformation; sites which still bore the traces of their own ruined pasts. I began to see sound as a prism through which to view these environments. Sound itself is unstable and discontinuous, but sound recordings gesture towards permanency. This tension between flux and stability seemed to speak to the complex entanglements of place, memory, history and archaeology that I was experiencing. Leaving instruments in particular places was my way of trying to momentarily incorporate them into the landscape, so that when I came to work with them, I was also working with the land itself. In this light, the instrument became a kind of emissary, not merely for myself but also for the land in which it temporarily resided; it became a kind of go-between.

But yes, on a very real, tangible level, transformations could occur, and it’s possible to see the changes that the environment visited upon my instruments in the same context as my own intentional modifications; both processes transformed the sound of each instrument, and, in extreme cases, damaged it beyond repair. Fundamental to both approaches is a concern with physicality and instability, with the passage of time and its corollaries. The physical artefact, therefore, becomes a device that dramatises those concerns. Much of my work has been concerned with examining different kinds of control, and of relinquishing that control. It’s also been about exploring other kinds of agency than simply my own. It may seem like a paradox, but if it was meaningful that I should play each of the instruments on my recordings, what if I myself became the instrument for other kinds of intentionality? Could I get out of the way sufficiently so that something else could come through?